By: Thomas Jackson, PT, DPT, Cert. DN, Cert. SMT

Popular exercise regimens often promote core strength as an essential component to fitness. In the medical profession, the core often is cited as the culprit for common conditions such as low back pain and poor posture.

Physical therapists are frequently tasked with improving a person’s core strength to decrease pain, improve posture, prevent injury and promote wellness. However, with countless core exercises available, it can be difficult to determine the best ones for a time-efficient training routine.

Anatomy of the core

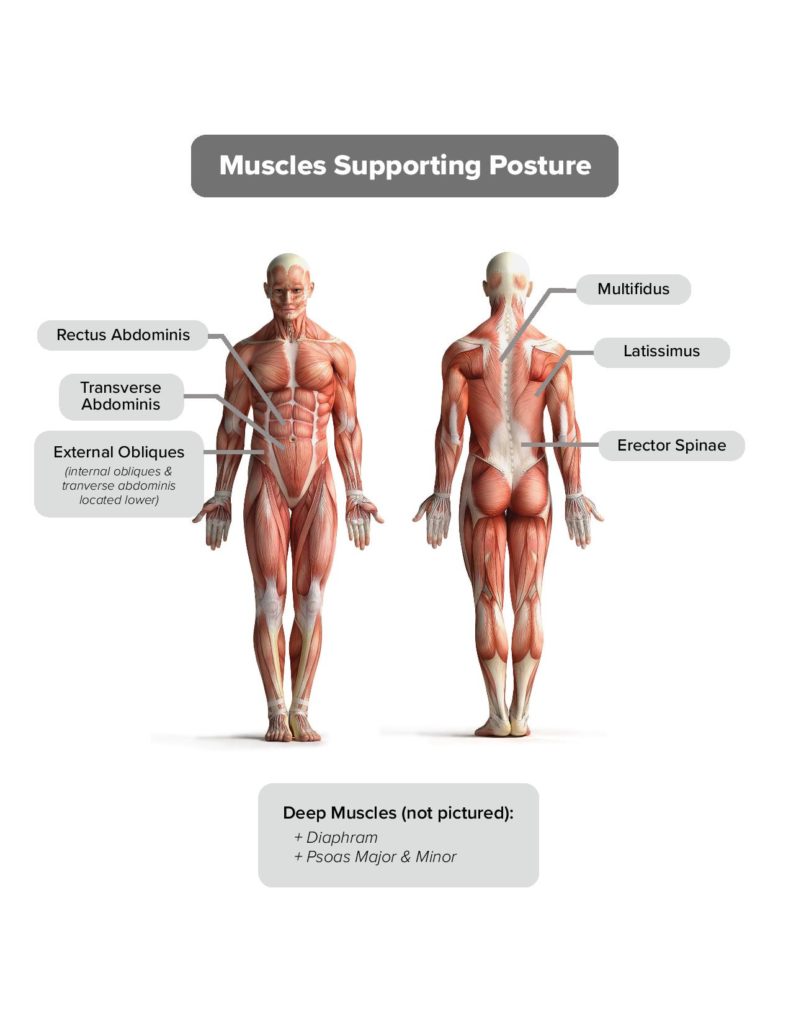

The core extends from the mid-thorax to the lower abdomen; it encircles the body’s internal organs from the diaphragm to the pelvis (Fig.1). The muscles pictured are commonly considered the core muscles, with several other muscles adding support to core strength.1

The rectus abdominis is responsible for bending the trunk forward, while the erector spinae bend the trunk backward. The internal and external obliques rotate the trunk. The transverse abdominis pulls the lower abdomen, or the area below the belly button, toward the spine, acting as an internal “belt” holding this area firmly in place.

These are the most commonly identified core muscles. They must be trained uniquely to produce a well-rounded core routine.

A lesser known structure for core support involves the attachment of the latissimus dorsi (Fig. 1) and gluteus maximus, or buttocks muscle, to the connective tissue of the low back.1 This connective tissue, called the thoracolumbar fascia, acts as a connection point for the lumbar spine to the surrounding supportive muscles, making training of the latissimus and gluteus maximus essential for core stability.

The most commonly overlooked muscle when it comes to core strength is the serratus anterior, which extends from the underside of the scapula (shoulder blade) to the side of the ribcage.2 It primarily pulls the scapula along the ribs. This movement is important to control whenever the arms accept weight to transfer to the torso, such as with lifting or push-up exercises.

Reducing injury risk

To develop a sufficient level of strength and stability to reduce the risk of injury, the core must be trained in all its components.

Though the core muscles perform certain functions, the purpose of core training is more to stabilize these motions rather than create them. This allows for development of control when moving the legs, arms and torso in many different planes as is common in daily activities.

For example, when performing a squat, the core prevents forward or backward tipping of the torso rather than flexing or extending the torso. As such, exercises to train core muscles most often involve sustaining positions against gravity or resistance to prevent movement.

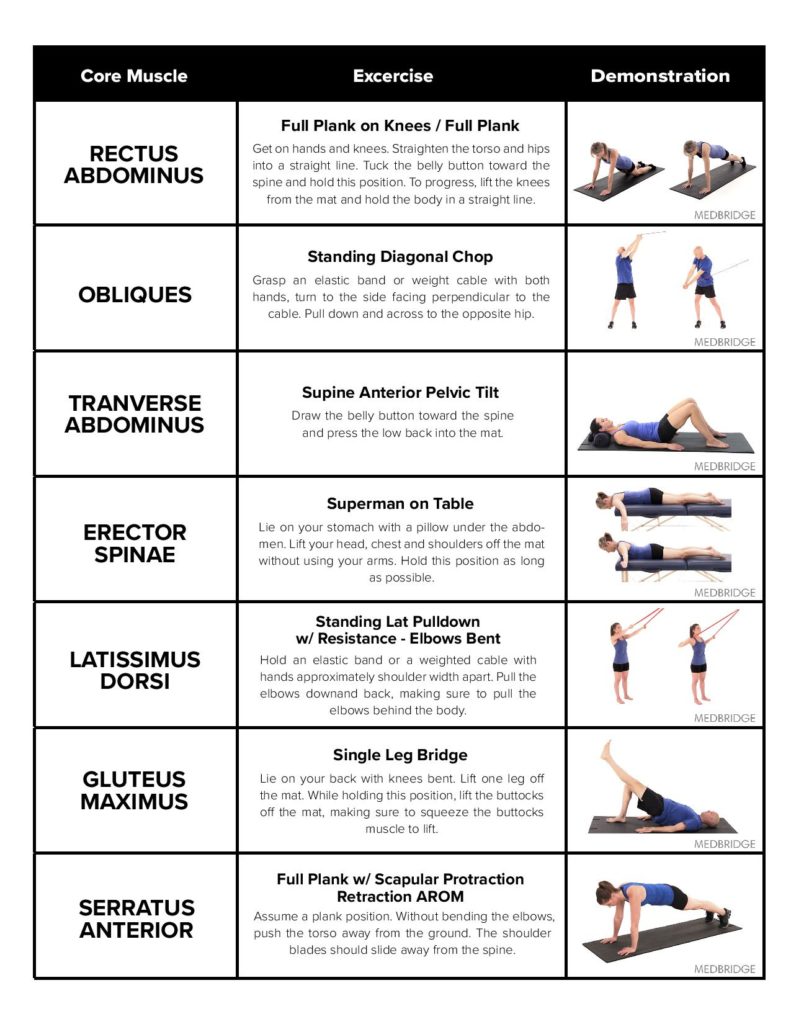

The exercises described below (Fig. 2) are simple, yet effective to train each core muscle. Each of these exercises can be sustained until failure for three to five repetitions.

Core strength is an integral part of fitness and injury prevention and should be incorporated into almost any fitness program. Core training can be challenging, however, and if pain persists while attempting to strengthen these muscles, it is best to consult a qualified specialist to assess form and musculoskeletal limitations. Physical therapists specialize in body movement and are uniquely trained to help people improve in these areas.

Fig. 1

Fig 2.

References

1. Karageanes, Steven J. (2004). Principles of manual sports medicine. Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins. pp. 510–511. ISBN 978-0-7817-4189-7. Retrieved March 14th, 2019

2. Decker, M. J., Hintermeister, R. A., Faber, K. J., & Hawkins, R. J. (1999). Serratus Anterior Muscle Activity During Selected Rehabilitation Exercises. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 27(6), 784–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465990270061601